This article was originally published in the Adjudication Society Newsletter.

Construction projects are complex undertakings that involve numerous stakeholders, substantial investments, and intricate processes.

The businesses that operate within the built environment are for the most part project driven businesses, meaning that the sum total of all projects undertaken impacts the commercial viability of that business.

With these layers of complexities, and the pressures for businesses to remain viable, we could say with some degree of confidence that the construction industry is primed for disputes.

We could also say that disputes are almost an inevitable part of this industry, due to the reasons mentioned above, amongst others.

Adjudication, since the time of the Latham report recommending adjudication as a process for resolving construction disputes, has become widely adopted both within the UK and globally.

It is understood that this global adoption is due to the advantages that the process offers, namely the costs and time scale benefits, especially by comparison to more legislative means of resolving differences

“It [adjudication] is not an alternative to anything: it is the only game in town” – (Coulson LJ)

However, like all dispute resolution processes, adjudication is bound by strict procedural protocols and principles, which are stipulated by the applicable legislation within the appropriate jurisdiction.

Adjudicators in training are taught these principles and procedures, along with the governing legislation that they must abide by, in order for their decisions to be enforceable.

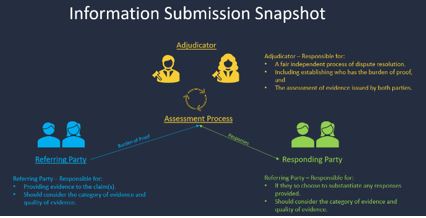

Two of those principles are that of “the burden of proof” and “how to assess evidence”, and adjudicators are also made aware of the consequences that are likely to be incurred should they not abide by these procedures.

It is the previously mentioned principles and rules of the adjudication process that will be considered in this article, and they will be considered from both an adjudicator’s perspective and the parties’ perspective, as we explore how to build your case with a dual perspective.

“If a dispute cannot be resolved first by the parties themselves in good faith, it is referred to the adjudicator for decision. Such a system must become the key to settling disputes in the construction industry.” – (Latham, 1994)

Jurisdiction & Legislation – A Source of Power

Adjudicators are bound by the applicable legislation to which the dispute must be settled within. Failure to observe the applicable legislation can result in challenges being made against the final award (decision).

With the growing worldwide adoption of adjudication, some jurisdictions vary in their application of the rules for adjudication. Within some countries such as Australia, the legislation differs even between States.

This highlights one crucial requirement, which is to ensure that you are working on the version of the legislation applicable to the contract under which you have been engaged.

This is not something that just the adjudicator should be concerned with, but also the parties to the adjudication.

The adjudicator will naturally become focused on the applicable legislation at the time of appointment; however, the parties need to be considering the applicable legislation as early as the conception stage of the project, especially if the project consists of international or even interstate elements.

The below table shows some of the different legislations in relation to adjudication

Table 1 – Example of Global Legislation Table (not exhaustive)

NB: The above referenced information may have changed since the time of this article being issued.

The key takeaway here is that regardless of your role within the adjudication process, you must know how the applicable law that applies to the adjudication, and also ensure you are dealing with the matters under the correct revision / amendments of the legislation.

Example of Challenge: Acting without Jurisdiction.

In Principal Construction Ltd v Beneavin Contractors Ltd [2021], the respondent sought to challenge the decision of the adjudicator on the grounds of acting without jurisdiction and sought to rely on a previous case as justification, however in reliance of the principles set out by Coulson J. in Pilon Ltd v Breyer Group Plc, Justice Meenan decided that the adjudicator had in fact acted within jurisdiction and natural justice. – (Principal Construction Limited v Beneavin Contractors Limited, 2021)

Burden of Proof

Whether in the jurisdictions of common law or civil, there is generic acceptance with respects to the principle of “burden of proof”, along with the presenting of evidence, albeit differences are present when we consider how the information provided, is to be treated. (CIArb, 2017)

At its core, and for matters of a contractual nature, the burden of proof rests with the claimant. Meaning that the claimant (or referring party) is required to prove the asserted facts. If the claimant fails in this regard the chances are the claim will fail.

For matters in issue relating to construction disputes, this is where solid commercial / contractual governance and project documentation will add value to the adjudication process.

Part of the adjudicator’s role is to understand who must satisfy the obligations of the burden of proof; those who must meet the obligations are expected to provide evidence to this effect.

Typically, evidence is submitted to the adjudicator via legal representation or representatives of the applicable party, for example: Directors, Commercial Directors or Managers.

It is advantageous for those that are required to provide evidence / substantiation, to understand the process of assessing evidence and what the adjudicator will be looking for.

“The burden of proof approach requires a claimant to show what part of the claimed loss has been caused solely by the defendant in order for substantial damages to be recovered in respect of it.” – (Stephen Frust, 2016)

Assessing Evidence

Although the rules for assessing evidence (particularly within the UK) are not binding upon the adjudicator, the adjudicator must understand the rules of evidence in order for his or her decision to be enforceable.

By doing so, this also contributes towards demonstrating that all matters have been considered by the adjudicator (from all parties) and the process has been fair, and natural justice has been applied.

Again, it is advantageous for the parties to the adjudication, to have an appreciation as to what the adjudicator will be looking for as he or she conducts the process.

From firsthand experience studying to become an adjudicator, aspiring adjudicators are advised as a minimum [and not exhaustively] to consider:

- What elements of the dispute do the parties agree on.

- Of the facts that are agreed as being in dispute, which party carries the burden of proof?

- What are the asserted facts by the referring party.

- What are the asserted facts by the responding party.

- Has evidence been provided to support the asserted facts.

- How will I categories the facts and evidence.

With this in mind, any party to an adjudication dispute, regardless of whether or not they are the referring party, should consider how the evidence they submit will be received and reviewed by the adjudicator.

Key point: Natural Justice defined

“The common law rules of natural justice or procedural fairness are two-fold. First, the person affected has the right to prior notice and an effective opportunity to make representations before a decision is made. Secondly, the person affected has the right to an unbiased tribunal.” – (AMEC Capital Projects Ltd V Whitefriars City Estates Ltd, 2004)

Categories and Quality of Supporting Information

Now that we have established there is an obligation to satisfy with respects to the burden of proof, and we know that the adjudicator will be guided by the rules of evidence, let’s explore how the evidence will likely be categorised and how the quality of information has a bearing on the procedure, this should provide the parties to the adjudication some elements for consideration prior to submitting any information be that under referral or response.

The categories of evidence:

- Documentary evidence: As most disputes referred to adjudication relate to issues of payment and / or delay, documentary evidence in the form of contracts, programmes, payment schedules, etc, are the most likely source of credible substantiation for any arguments raised.

- Oral evidence: Is evidence provided as testimony, although this is usually used by the Courts rather than adjudication. Therefore, in relation to adjudication, it is common for the parties to rely more on the documentary evidence.

- Expert Evidence: Expert evidence can have quite the impact on the adjudicator’s final decision, as this type of evidence is provided by an SME (Subject Matter Expert) who will provide opinion based on facts within the limits of their instructions.

The expert will likely take complex technical information and present his or her findings in a way to aid the adjudicators’ understanding of the matters in issue.

“This has been found to be of great use in informing each party of the case to be advanced by the other side, and in facilitating the narrowing of issues” – (Uff, 2009)

- Real Evidence: Is physical evidence that can be presented by the parties and reviewed by the adjudicator, for example a site inspection that may serve as a means of providing evidence via examination of a physical issue, thus supporting purported facts.

Quality of Evidence:

It should be somewhat obvious that the better the quality and credibility of information you submit, the greater the chances are of you winning your particular point(s) of the dispute, however this is not always the case, and furthermore the parties sometimes do not always submit the best quality information for assessment.

Based on the aforementioned categories of evidence, and from personal experience, the standard evidence packages submitted by the parties typically consists of documentary evidence, witness evidence in the form of statutory declaration(s), and expert evidence in the form of independent report(s).

But how do the parties ensure they are submitting quality evidence?

And what should you consider prior to submission?

What to Consider Prior to Submitting Evidence

Consideration of the quality of project / commercial information / data, should be at the forefront of all project & commercial managers minds, from as early as the tender stage of the works.

How businesses set up their data capture, change management and contractual processes can massively aid the dispute process should the need ever arise.

Below are some basic guidelines to follow when considering how to establish quality within commercial documentation:

- Accuracy & Reliability: Is your information reliable? Will it stand the test of scrutiny by the adjudicator?

If your answers are yes, then chances are you have a document worthy of issue.

Ask an independent third party to review the information, in efforts to avoid a prejudice assessment.

- Credibility: Is the source of the information credible. It has been said (although in relation to witnesses), that a credible witness will outweigh any number of non-credible witnesses. A principle that still stands when dealing with documentary evidence.

“There is an old maxim in law, one credible witness outweighs any number of other witnesses” – (Barry, 1994) (Citing The Wega [1895])

- Detailed records: this will aid in supporting challenges or questions of credibility, if your records are in order and information can be provided swiftly, this will provide a greater sense of authority on the matter.

- Clarity: Given the adjudication process is to be swift, and is time pressured, clarity of information is a must. Your information wants to be such that the adjudicator can clearly understand what you have submitted and why, without unnecessarily creating more questions.

- Consistency: Submitting conflicting information can hinder your position and cost time, ensure you have consistency and cross support throughout your submissions.

- Compliance: where applicable demonstrate your contractual compliance, and compliance towards any implied terms.

- Relevance: Stick to the matters in issue and avoid introducing information that could detract from the matter(s) in issue.

- Remove the emotion: It is easy when the pressure is on to become emotional, however emotions have no place in commercial communications, and this could hinder your position, remain neutral.

Conclusion

In conclusion, from the burden of proof to the critical assessment of evidence, every facet of the adjudication process underscores the need for conformity, compliance, clarity and credibility.

All of which can be achieved via the use of quality, credible, solid commercial / project related documentation.

Whether the parties choose to provide documentary evidence, expert evidence, or real evidence, the submissions must support the claims or defence thereof, and consideration must be given to the amount of scrutiny the adjudicator will apply within his or her role.

Just like construction projects themselves, navigating the complexities of disputes demands a meticulous approach, especially to providing evidence and likewise procedural compliance by all parties.

As professionals in this dynamic industry, we must not be remiss in our professional duties and understandings of the process of the adjudication.

Front end investment into factors such as change management, data capture and contractual governance could pay real dividends for business leaders should the risk of a dispute reach a state of fruition.

Finally, ensure that you are aware what your rights are with respect to the right to adjudicate and the relevant legislation that applies.

References

AMEC Capital Projects Ltd V Whitefriars City Estates Ltd, 2004/0558 (Supreme Court of Judicature Court of Appeal (Civil Division) On Apreal from Technology and Construction Court October 28, 2004). Retrieved July 2024, from https://www.bailii.org/cgi-bin/format.cgi?doc=/ew/cases/EWCA/Civ/2004/1418.html&query=(Dyson)+AND+(LJ)+AND+(Amec)+AND+(Whitefriars)+AND+(2004)+AND+(natural)+AND+(justice)

Barry, J. (1994). The Method of Judging. 3. Townsville, Queensland. Retrieved July 2024, from https://classic.austlii.edu.au/au/journals/JCULawRw/1994/7.pdf

CIArb. (2017). The Process and Drafting, Evidance and Decision Writing. 48/134. Retrieved 2024

Latham, S. M. (1994, July). Constructing The Team. doi:ISBN 0 11 752994 X

Principal Construction Limited v Beneavin Contractors Limited (July 16, 2021). Retrieved July 2024, from https://www.bailii.org/cgi-bin/format.cgi?doc=/ie/cases/IEHC/2021/2021IEHC578.html&query=(construction)+AND+(adjudication)+AND+(challenge)+AND+(jurisdiction)

Stephen Frust, V. R. (2016). Keating on Construction (10 ed.). London: Sweet & Maxwell. Retrieved July 24, 2024

Uff, J. (2009). Construction Law (10 ed.). London: Sweet & Maxwell. Retrieved July 2024

Table 1Example of Global Legislation Table (not exhaustive) 3